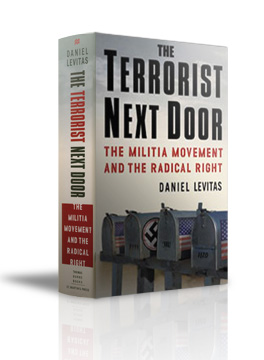

Read Daniel Levitas on the history of antisemitism in the United States as published in the 1999-2000 edition of Groliers Multimedia Encyclopedia.

Copyright Groliers Multimedia Encyclopedia 1999-2000

Anti-Semitism in the United States Like other religious minorities, the first Jews who arrived in colonial America faced significant barriers to civic, political, and religious participation. When 23 Portuguese Jews from Brazil arrived in what is now New York in 1654, Peter Stuyvesant, the governor of New Amsterdam, tried to prevent them from staying. Although allowed to remain, these Jews were banned from public worship, buying land, holding public office, trading with Native Americans, working as craftsmen, or engaging in retail trade. The attitudes of Stuyvesant and his fellow colonists toward Jews were rooted in the centuries-old European anti-Semitism, which had depicted Jews as the killers of Christ, agents of the Devil, and murderers of Christian children. In addition, hateful religious stereotypes had labeled Jews as scheming, cruel, corrupt, dishonest, greedy, and unclean.

The 17th-19th Centuries

The 250 or so Jews that populated North America in the 17th century faced numerous restrictions, including bans on practicing law, medicine, and other professions. As late as 1790, one year before adoption of the Bill of Rights, several states had religious tests for holding public office, and Connecticut, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and South Carolina still maintained established churches. Between 1789 and 1792, Delaware, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, and Georgia eliminated barriers that prevented Jews from voting, but it took longer in Rhode Island (1842), North Carolina (1868), and New Hampshire (1877). Despite these restrictions, which were often applied unevenly, there were really too few Jews in 17th- and 18th-century America for anti-Semitism to become a significant social or political phenomenon at the time. And the evolution from toleration to full civil and political equality for Jews that followed the American Revolution helped ensure that anti-Semitism would never become official government policy, as it had in Europe.

By 1840, Jews constituted a tiny, but nonetheless stable, middle-class minority of about 15,000 out of the 17 million Americans counted by the U.S. Census. Jews intermarried rather freely with non-Jews, continuing a trend that had begun at least a century earlier. However, as immigration increased the Jewish population to 50,000 by 1848, negative stereotypes of Jews in newspapers, literature, drama, art, and popular culture grew more commonplace and physical attacks became more frequent. By the time of the Civil War, tensions over race and immigration, as well as economic competition between Jews and non-Jews, combined to produce the worst outbreak of anti-Semitism to that date. Americans on both sides of the slavery issue denounced Jews as disloyal war profiteers, and accused them of driving Christians out of business and of aiding the enemy. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant was influenced by these sentiments when he issued General Order No. 11 on Dec. 17, 1862, banishing all Jews from western Tennessee, but President Abraham Lincoln rescinded the order.

Overt expressions of anti-Semitism subsided after the war, but continued immigration, as well as the upward mobility of some Jews, provided a persistent focal point for anti-Jewish propaganda and action. By 1880 the Jewish population had increased to around 230,000, and non-Jews responded by developing a full-fledged system of social exclusion, including discriminatory laws, covenants, and other barriers to social mobility. In one famous incident in 1877, Joseph Seligman, a German-Jewish banker and friend of the late President Lincoln, was barred from registering as a guest at the posh Grand Union Hotel in Saratoga Springs, N.Y. Beginning in the early 1880s, declining farm prices also prompted elements of the Populist movement (see Populist party) to blame Jewish financiers for their plight. Although Jews played only a minor role in the nation’s commercial banking system, the prominence of Jewish investment bankers such as the Rothschilds (see Rothschild, family) in Europe, and Jacob Schiff, of Kuhn, Loeb and Co. in New York City, made the claims of anti-Semites believable to some.

From the Frank Lynching to World War II

Continued pogroms in eastern Europe, particularly Russia, prompted yet another wave of Jewish immigrants after 1881. American groups like the Immigration Restriction League, founded in 1894, criticized these new arrivals along with immigrants from Asia and southern and eastern Europe, as culturally, intellectually, morally, and biologically inferior. (Thirty years later, in 1924, Jewish immigration was reduced to a trickle when Congress finally passed stiff immigration quotas.) By 1905 the Jewish population was 1.5 million, and rising prejudice prompted the formation of the American Jewish Committee the following year. In 1913 the Jewish fraternal group B’nai B’rith set up the Anti-Defamation League to fight discrimination. That was also the year in which Leo Frank, a transplanted Jewish New Yorker and the manager of a pencil factory in Marietta, Ga, was convicted of the rape and murder of one of his employees, 13-year-old Mary Phagan, although he was innocent of the crime. Frank’s trial was conducted in an atmosphere of anti-Semitic hysteria, and Jewish groups protested vigorously. Shortly after Georgia governor John M. Slaton commuted Frank’s death sentence to life imprisonment, Frank was abducted from a prison farm and lynched, on Aug. 16, 1915. (Frank was posthumously pardoned by Georgia governor Joe Frank Harris in 1986.)

The Frank lynching coincided with and helped spark the post-Civil War revival of the Ku Klux Klan. With its call for “100 Percent Americanism,” and its fundamental message of white supremacy, the Klan capitalized on anti-immigrant, anti-Catholic sentiment, as well as fears that anarchists, communists, and Jews were subverting American values and ideals. At its peak in the early 1920s, the Klan had as many as 3 to 4 million members before it declined to around several hundred thousand in 1928.

In 1920 the Dearborn Independent, a weekly newspaper financed by automobile magnate Henry Ford (see Ford, family), began publishing a series of 91 consecutive articles that attacked Jews as worldwide agents of Bolshevism and accused them of corrupting virtually every aspect of American society. Republished in book form as The International Jew: The World’s Foremost Problem, the articles were the most significant piece of anti-Semitic propaganda to appear in the United States to that date. According to critics, the articles also constituted an Americanized version of the notorious Protocols of the Elders of Zion, a document forged in Europe that purported to be a blueprint for Jewish world control.

The widespread pattern of social discrimination against Jews that had emerged following the Civil War intensified during the first half of the 20th century. Newspaper advertisements for resorts, jobs, and housing that specified “Christians only” need apply proliferated in the 1920s. Employment discrimination became more pervasive in the years immediately before World War I as more Jews sought white-collar jobs. Quotas on the number of Jews admitted to medical schools, colleges, and universities followed in the 1920s, first at Ivy League schools in the Northeast and then elsewhere.

During the 1930s and 1940s, right-wing demagogues such as the Rev. Gerald L. K. Smith, Father Charles Coughlin, William Dudley Pelley, and the Rev. Gerald Winrod linked the Depression of the 1930s, the New Deal, President Franklin Roosevelt, and the threat of war in Europe to the machinations of an imagined international Jewish conspiracy that was both communist and capitalist. Smith, a Disciples of Christ minister, was the founder (1937) of the Committee of One Million and publisher (beginning in 1942) of The Cross and the Flag, a magazine that declared that “Christian character is the basis of all real Americanism.” Coughlin was a Roman Catholic priest who endorsed The Protocols of the Elders of Zion and praised Nazi Germany. His weekly radio audience ranged between 5 and 12 million listeners throughout the late 1930s, and his newspaper Social Justice reached 800,000 people at its peak in 1937 but was banned from the mail during the war. William Dudley Pelley founded (1933) the anti-Semitic Silvershirt Legion of America; nine years later he was convicted of sedition. And Gerald Winrod, leader of Defenders of the Christian Faith, was eventually indicted for conspiracy to cause insubordination in the armed forces during World War II.

Despite wartime propaganda that attacked Nazism and race hatred in specific terms, and government prosecutions of extremists like Pelley and Winrod, anti-Semitism was widespread. In one 1938 poll, 41 percent of respondents agreed that Jews had “too much power in the United States,” and this figure rose to 58 percent by 1945. Although only 0.6 percent of the nation’s 93,000 commercial bankers in 1939 were Jewish, the idea that Jews controlled the banking system remained a popular myth. Political anti-Semitism also was high during the war years, with 23 percent of respondents in one 1945 survey saying they would vote for a congressional candidate if the candidate declared “himself as being against the Jews” and as many as 35 percent saying it would not affect their vote. Jews also noted the influence of anti-Semitism when the U.S. State Department opposed efforts to lower immigration barriers to admit Jews and other refugees fleeing the Holocaust and Nazi-occupied Europe.

Postwar Attitudes

Although anti-Semitism began declining in the years following World War II, persistent job discrimination still meant that Jews were vastly underrepresented in management in heavy industry, banking, transportation, insurance, and other fields into the 1950s. The rise of McCarthyism (see McCarthy, Joseph R.) and deepening of the cold war in the early 1950s also prompted some Jewish organizations to express concern that anti-Semites were gaining respectability by associating with the anti-Communist movement. The Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas (1954) to desegregate public schools invigorated many groups that opposed equal rights for blacks and espoused anti-Semitism, particularly in the South. Between Jan. 1, 1956, and June 1, 1963, the Ku Klux Klan was suspected of at least 138 dynamite bombings of black residences, churches, synagogues, and integrated facilities across the South.

Sociological studies in the early 1960s revealed that while some aspects of anti-Semitism had declined markedly since the 1930s and ’40s, stereotypes of Jews as unethical, dishonest, aggressive, pushy, clannish, and conceited were widely held among approximately one-third of Americans. But researchers also found very little support for actual discrimination. Only 4 percent of Americans surveyed in 1962 said they thought colleges should “limit the number of Jews they admit,” compared to 26 percent in 1938, and only 3 percent said they would prefer not to have a Jewish neighbor, compared to 25 percent in 1940. Despite this trend, as many as 28 percent of Americans surveyed in the early 1960s defended the rights of social clubs to exclude Jews, and 29 percent offered only token opposition to such policies. And 51 percent of Americans in 1964 agreed with the statement that Jews should “quit complaining about what happened to them in Nazi Germany.” Anti-Semitism continued to decline after 1964, but another comprehensive study launched by the American Jewish Committee in 1981 still found anti-Semitism to be a “serious social problem.” The report also noted a substantial increase since 1964 (23 percent versus 13 percent) in the number of non-Jews believing that Jews have “too much power in the United States.” Analyzing the decline in other anti-Semitic attitudes, researchers concluded that the growing proportion of younger, less prejudiced individuals in the population was largely responsible for the trend.

A comprehensive national survey conducted by the Anti-Defamation League in 1992 found 20 percent of Americans–between 35 and 40 million adults– holding unquestionably anti-Semitic views, but those numbers had declined markedly six years later when another ADL study classified only 12 percent of the population–between 20 to 25 million adults–as “most anti-Semitic.” Confirming the findings of previous surveys, both studies also found that African Americans were significantly more likely than whites to hold anti-Semitic views, with 34 percent of blacks classified as “most anti-Semitic,” compared to 9 percent of whites in 1998.

In a 1967 New York Times Magazine article entitled “Negroes are Anti-Semitic Because They’re Anti-White,” the famous African American author James Baldwin sought to explain the prevalence of black anti-Semitism. Recent data, however, suggest that the phenomenon is more complex and not necessarily that well understood. As with the broader public, the overall level of anti-Semitism among blacks has declined over the last three decades, but the decline has been slower among blacks than among whites. And, although the 1998 ADL survey found a strong correlation between education level and anti-Semitism among African Americans, blacks at all education levels were still more likely than whites to accept anti-Jewish stereotypes. These have figured prominently in the rhetoric of some black leaders, most notably the influential Louis Farrakhan.

The 1998 ADL survey also found a correlation between anti-Semitism and sympathy for right-wing antigovernment groups. Although anti-Semitism has declined over the past 35 years, the activities of some anti-Semitic groups have intensified. From 1974 to 1979, membership in the Ku Klux Klan rose from a historic all-time low of 1,500 to 11,500, and throughout the 1980s various Klan factions allied themselves with more explicitly neo-Nazi groups like the Aryan Nations (see neo-Nazi movements). The founding (1979) of the California-based Institute for Holocaust Review helped popularize the anti-Semitic notion that the Holocaust was a hoax. Farm foreclosures and economic distress in the rural Great Plains and Midwest during the mid-1980s prompted organizers for groups like the Posse Comitatus to spread anti-Semitic rhetoric throughout rural America. From 1986 to 1991 the numbers of neo-Nazi skinheads grew tenfold, reaching approximately 3,500 distributed among more than 35 cities. And the mid-1990s saw the formation of paramilitary citizens’ “militias” (see militia movement), many of which were accused of circulating anti-Semitic conspiracy theories and preaching religious bigotry.

Escalating hate crimes targeting Jews and other minority groups prompted passage of the federal Hate Crimes Statistics Act in 1990 and spurred 41 state legislatures, as of 1998, to enact a patchwork of laws providing for police training about bias crimes, stiffer jail terms for perpetrators, and mandatory hate-crimes data collection by law enforcement. From 1979 to 1989 the ADL recorded more than 9,617 anti-Semitic incidents, including 6,400 cases of vandalism, bombings and attempted bombings, arsons and attempted arsons, and cemetery desecrations. The tally peaked at 2,066 in 1994, but declined over the next three years, consistent with the downward trend in national crime statistics. According to 1996 Federal Bureau of Investigation statistics, of 8,759 hate crimes recorded that year, 13 percent were anti-Semitic.

Daniel Levitas

Bibliography:

Dinnerstein, Leonard, Anti-Semitism in America (1994) and, as ed., Anti-Semitism in the United States, (1971);

Gerber, David A., ed., Anti-Semitism in American History (1986);

Quinley, Harold E., and Glock, Charles Y., Anti-Semitism in America (1979);

Saloman, George, ed., Jews in the Mind of America (1966);

Selznick, Gertrude J., and Steinberg, Stephen, The Tenacity of Prejudice: Anti-Semitism in Contemporary America (1969);

Smith, Tom W., Working Papers on Contemporary Anti-Semitism: Anti-Semitism in America (1994);

Tobin, Gary A., and Sassler, Sharon L., Jewish Perceptions of Anti-Semitism (1988).